Do you think happy 100 year olds in Greece got that way with extensive food journals and continuous glucose monitors?

I asked this question, referencing the healthy and long-lived residents of Ikaria, Greece, one of the five Blue Zones, on my Instagram feed back in December. There were 87 “content interactions” on the post, which is about .06% of my followers. The algorithm is notoriously hard to crack over there and I’m not terribly worried about low interaction, but it made me wonder if the question I was asking us all to consider is a pretty unpopular one right now? We live in the era of wearable health trackers and “what gets measured, gets managed” mantras, so it wouldn’t necessarily be an unreasonable conclusion.

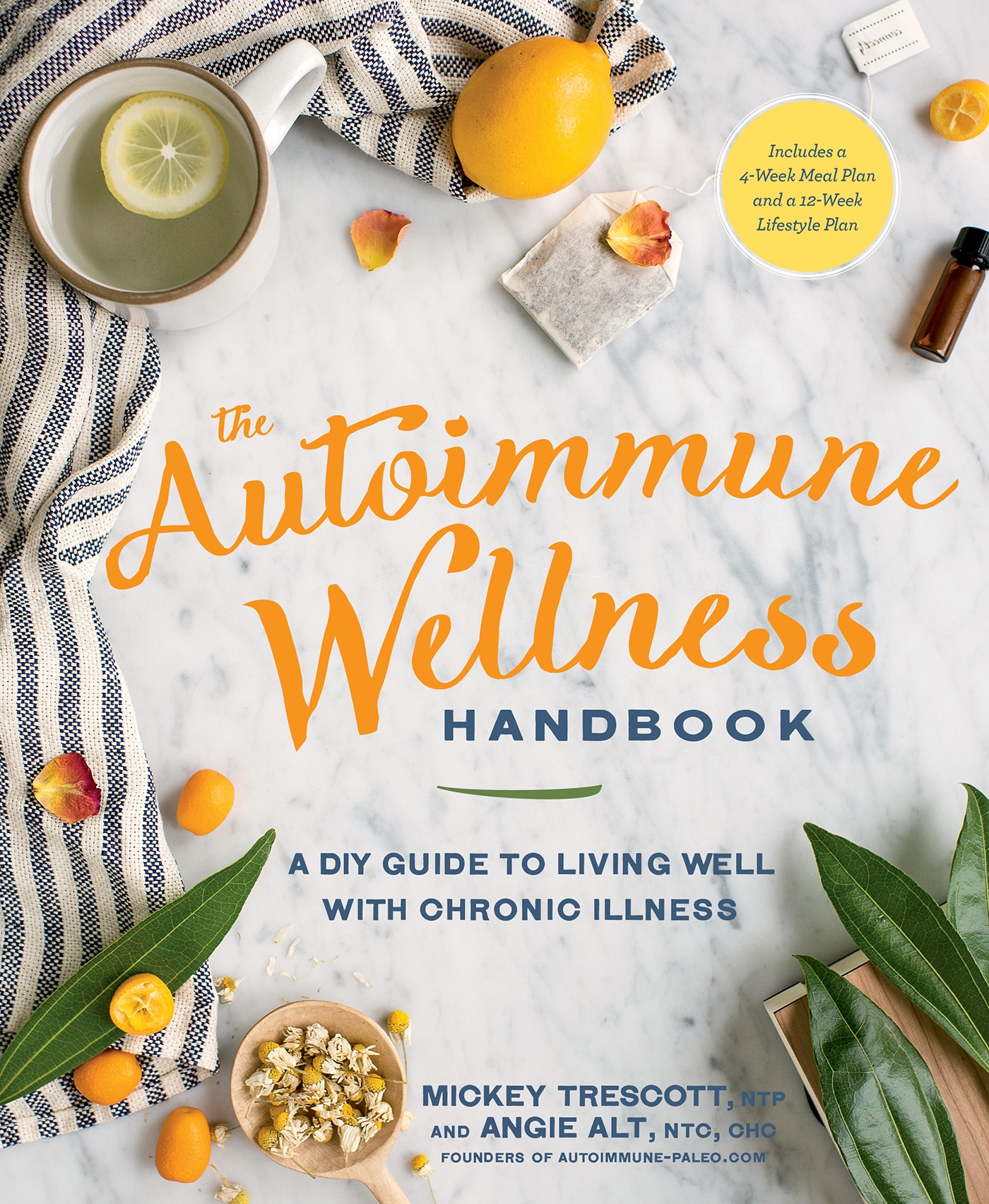

I’ve been mulling it over ever since and decided that writing about it for Autoimmune Wellness was a good opportunity to dive deeper.

Health Trackers Defined

To explore this topic, I think it’s important to first clarify exactly what I mean when I refer to “wearable health trackers,” since there are so many different types. A broader term I came across via Insider Intelligence, is “wearable health technology.” They defined wearable health technology as, “ . . . electronic devices that consumers can wear and are designed to collect the data of users’ personal health and exercise.” Replacing the word “tracker” with “technology,” helps clarify that these devices are moving beyond some of the early fitness focused devices that were simply wristband pedometers tracking steps and into implanted monitors that measure everything from temperature and heart rate to blood sugar levels. When I use the term “tracker,” I’m really referring to this broader category.

Examples of this kind of technology are:

- Fitness trackers, like the early FitBit, that monitor steps and heart rate.

- Smart watches, like the Apple watch, which measures blood oxygen saturation, sleep, and even has an electrocardiogram (ECG) sensor.

- ECG monitors, like Move ECG, which has an electrocardiogram sensor that can detect atrial fibrillation (an irregular, rapid heart rhythm that can cause blood clots in the heart) and can send the reading to your doctor.

- Blood pressure monitors, like HeartGuide, which is an oscillometric (a blood pressure measurement principle) blood pressure monitor that can measure blood pressure and daily activity and has the option to send readings to an app for review, comparison, and treatment optimization.

- Sleep trackers, like Oura Ring, which track sleep patterns, including time in specific sleep stages and other metrics and then makes recommendations via an app for planning your daily activities.

- Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), like the Freestyle Libre, which uses a sensor wire inserted under the skin to measure interstitial glucose (blood sugar in the fluid between cells) and then transmits the data so that glucose levels and trends can be displayed.

- Biosensors, like Philips Biosensor BX100, which is a wearable patch that measures many different vital signs and so far appears to only be used in clinical settings.

Insider Intelligence also reported, just a few weeks ago, that in the last four years US consumer use of wearables increased from 9% to 33% and that trend is predicted to continue. So, what’s the hope of these devices?

The Hope Behind Wearable Health Trackers

I think Dr. Andrew Weil, well-known pioneer of integrative medicine, articulates best the original hope of what we might call the “first generation” trackers. He said in a 2017 article offering guidance on their safety, “ . . . anything that helps motivate inactive people to get up and move – and meet realistic goals aimed at enhancing health – would certainly be worthwhile.” Anything that helps keep us engaged in our own health and wellness is worth a shot, right?

Dr. Weil’s statement was and is still shared by many others in healthcare. For instance, a cardiology practice in Colorado shares an article on their website emphasizing that heart doctors advocate diet and exercise for their patients and trackers are useful for reaching those goals. The article particularly referenced “personal accountability, individually-tailored goals, and group motivation” as some of the benefits.

It’s no wonder that healthcare providers are supportive of trackers. The benefits in terms of healthcare delivery are undeniable, particularly with monitors like CGMs. One research review noted, “The innovation of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) may help to alert medical caregivers with regard to the development of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, which may decrease the potential complications in patients in the ICU.” The review made clear that the most serious of these “complications” was death. There’s no question that CGMs could be hugely beneficial for proper diabetic care.

The pandemic also changed how important wearable health trackers have become to healthcare delivery, not just for providers themselves, but also for the public acting on the information. Business Insider reported that tracker use skyrocketed in 2020 with the onset of the pandemic and in 2021 they estimated that more than one-fifth of the US population would start using a wearable device, “ . . . as the behavior to monitor health amid the pandemic continues to grow.” A study published in Nature Biomedical Engineering in late 2020 showed that data from smartwatches could be used to detect COVID-19 infection while the wearer was still pre-symptomatic. The researchers analyzed physiological and activity data from 32 individuals infected with COVID-19, finding that 26 of them (or 81%) had alterations in their heart rate, number of daily steps, or time asleep compared to their normal baselines. In four of the cases detection of the abnormal variation occurred at least nine days before symptom onset, an important finding in terms of trying to control the spread of a novel virus.

Even though the technology behind trackers has greatly expanded since the “first generation” varieties and become integral to healthcare itself, it ultimately seems that the hope of tracker use comes back to the Dr. Weil statement about motivation. Today “75% of users agree that wearables help them engage with their own health.” But there are voices raising concerns about the risks too.

The Risks of Using Health Trackers

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, the Senior Faculty Editor at Harvard Health Publishing shared a teaching from one of his medical school professors that sums up what a lot of the voices raising concerns over trackers are expressing, “Just because you can measure something doesn’t mean you should.”

The teaching from his medical school professor was shared in an article Shmerling wrote on whether or not CGMs are worthwhile for people without diabetes, where he pointed to a multi-center prospective study of 153 non-diabetic people, ranging in age from 7-80 years old, who wore a CGM for 10 days. The study found that 96% of the time their blood sugar levels were normal and that many of the “non-normal” readings were considered a mistake.

Mistakes do happen with CGMs. In fact, the National Institutes of Health recommends that diabetics use a finger-prick blood sugar measure twice a day to compare against the CGM. Levels, a health tech company that uses CGM data to “unlock your metabolic health,” claims (without citation) on their site the error margin or MARD (an acronym for “mean absolute relative difference”) between the CGM their company supports, the Freestyle Libre, and a blood draw measurement is 9.2%.

The reasons for this error margin are being hashed out in the research. One issue pointed out in a 2017 study is that CGMs don’t measure actual blood glucose changes, but instead glucose changes in the interstitial fluid. Interstitial fluid is the fluid between skin cells that the sensor wire in the device can access. The glucose levels in interstitial fluid lag behind blood glucose levels. There are also researchers saying the MARD values used to assess CGM accuracy are not straightforward and should be rethought.

Additionally, a review from doctors at The Ohio State University found evidence that CGMs may especially lack accuracy for detecting hypoglycemia (low glucose). I found this especially interesting, because avoiding low blood sugar symptoms is something I’ve heard cited as the basis for people, especially in the chronic illness community, wanting to utilize CGMs in the first place.

All of this to say, could that error margin lead to unnecessary anxiety, especially for non-diabetic users who may have much less understanding and plain old practice monitoring their blood sugar?

Concern about tracker risks doesn’t stop with CGMs though. Kelly G. Baron, PhD, a sleep disorders researcher warns about “orthosomnia.” In a series of case studies presented in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine Baron and other researchers shared that “. . . sleep professionals have been wary of incorporating these devices into treatment because of low concordance with polysomnography [a comprehensive sleep study] and actigraphy [a validated method of objectively measuring sleep parameters and average motor activity].” Further concern arose when they noticed an increasing number of patients who were anxiously seeking treatment for sleep issues based on perfectionist expectations that came from obsessing over their sleep tracking device data. Dr. Baron says that “ . . . a sign that your sleep tracker is getting in the way of actual sleep is if you put more stock into what the app says than how you actually feel. In the end, I think people need to realize that [trackers] are an estimation of your sleep . . . across the board, the claims of the devices go far beyond what they’re able to actually do.”

But, don’t you teach tracking?

It’s true! As a health coach, I do teach people how to utilize food and symptom journaling, a very low tech version of trackers. I’ve also partnered with medical researchers, which automatically requires tracking, especially in dietary studies. And I consult with health tech startups. I realize the red flag I’m raising may seem misaligned with my actual work.

I do, however, share the risk concerns over the level of accuracy, appropriateness for all groups, and anxiety-inducing side effects of the doctors and researchers presented above. For years, I’ve even taught my health coaching group members and individual clients to use modified approaches to food and symptom journaling, because I observed how triggering and paralyzing even those very low tech options could become. The risks can be serious and tracking of any sort, and especially the constant stream of data from wearable tech, should be approached with a lot of caution.

Here’s the parameters I follow for utilizing health tracking in my professional work:

- I work exclusively, in all the settings named, with people who are managing autoimmune diseases. If and when we track, it’s with the goal of solving an actual problem, not biohacking our way into becoming an impervious, “high-performing,” super-sexy immortal (aka, Vampire).

- When I work with individuals and group members, I encourage limited tracking for key periods to gather actionable data. The modified approach I like is to: a) establish a baseline, b) check in with a new short period of tracking to assess progress, if a pivot is required, or to make a comparison after implementing a new approach, and c) extend the tracking period only to identify patterns or connections.

- If folks I’m working with want to utilize wearables, I encourage them to evaluate their relationship to the data. For some, it can be positive and actionable, but for others it’s triggering. It’s important to “know thyself.”

- In the research and startup space, I’m an advocate for leveraging data collected from individuals during key periods, to help us learn something new and actionable for a whole group. In these settings, it’s not on the individuals to process all that information, which equates to less risk of it becoming paralyzing.

Observations

I’ve witnessed lots of friends and clients in the autoimmune community do really well with tracking, leveraging the information to optimize their healing process. I’ve also observed people who became obsessive and rigid with trackers. There seems to be many of us wrestling with paralyzing perfectionism in the autoimmune community and the constant data from the trackers can feed the internal dialogue about “getting the perfect score.” A close friend in the community even shared with me that although she’s not typically prone to tracker anxiety, she noticed while experimenting with a CGM that it could easily get out of control.

As a coach, I’ve even seen extreme cases where the CGM data brought disordered eating tendencies to the surface and a device the person wanted to use to aid a healing journey undermined progress significantly. This isn’t actually too much of a surprise. Healthy blood sugar control is crucial for staying alive and concern that one’s levels are poor can cause significant distress. It’s well-known in the medical community that diabetics, in attempting to control their blood sugar, can develop diabetes distress. This is stress specific to living with diabetes and it “ . . . may be both a precipitant and a consequence of eating disorders.” The National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) defines Type 1 diabetes as a risk factor for developing an eating disorder. Research has found that approximately one-quarter of women diagnosed with type one diabetes will develop an eating disorder. If diabetics, who legitimately must monitor blood sugar constantly and develop skills for doing that, are at this level of risk, imagine how much it impacts those who aren’t accustomed to this constant data?

Final Thoughts on Heath Trackers

I’m not shaming those who feel wearable trackers (or tracking of any kind) have been a win, but I am saying we should all be careful about where incorporation of these devices could lead.

There’s something else too . . . many, many people on this planet will never have access to wearables of any kind and might be struggling to access food at all. More data for these people is, frankly, insulting. The tracker industry is booming, but we haven’t even addressed a foundational equity issue yet.

The things I’m thinking about these days are:

- Is all the tracking helping?

- Is it sophisticated analysis? Or just anxiety-inducing?

- Is it solving or creating a health problem?

- Is this really what we need to focus on in order to be happy, healthy, and live well into old age?

You are not a robot. Track accordingly.

Tell me, community, how do you feel tracking, wearable or not? What have been your experiences?

References

- Ikaria, Greece – blue zones. Blue Zones – Live Better, Longer. (2021, May 4). Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.bluezones.com/exploration/ikaria-greece/#

- Phaneuf, A. (2022, April 15). Wearable tech in Healthcare: Smart Medical Devices & Trends in 2022. Insider Intelligence. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.insiderintelligence.com/insights/wearable-technology-healthcare-medical-devices/

- How safe are fitness trackers? – Andrew Weil, M.D. DrWeil.com. (2017, July 31). Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.drweil.com/health-wellness/balanced-living/exercise-fitness/how-safe-are-fitness-trackers/

- Cupps, R. (2016, May 12). Fitness tracker benefits: The what and why. South Denver Cardiology. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://southdenver.com/fitness-tracker-benefits/

- Sun, M.-T., Li, I.-C., Lin, W.-S., & Lin, G.-M. (2021). Pros and cons of continuous glucose monitoring in the Intensive Care Unit. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 9(29), 8666–8670. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8666

- Phaneuf, A. (2021, May 21). 5 examples of popular wearable devices in Healthcare. Business Insider. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.businessinsider.com/5-examples-wearable-healthcare-devices-2021-5

- Mishra, T., Wang, M., & Metwally, A. A. et al. (2020). Pre-symptomatic detection of covid-19 from smartwatch Data. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 4(12), 1208–1220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-020-00640-6

- Shmerling, MD, R. H. (2021, June 11). Is blood sugar monitoring without diabetes worthwhile? Harvard Health. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/is-blood-sugar-monitoring-without-diabetes-worthwhile-202106112473

- Shah, V. N., DuBose, S. N., & Li, Z. ,et al. (2019). Continuous glucose monitoring profiles in healthy nondiabetic participants: A multicenter prospective study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 104(10), 4356–4364. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-02763

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Continuous glucose monitoring. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/managing-diabetes/continuous-glucose-monitoring

- Levels Health, I. (n.d.). Sensor accuracy – CGM vs Finger Prick glucometer. Levels Support. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://support.levelshealth.com/article/63-sensor-accuracy

- Siegmund, T., Heinemann, L., Kolassa, R., & Thomas, A. (2017). Discrepancies between blood glucose and interstitial glucose—technological artifacts or physiology: Implications for selection of the appropriate therapeutic target. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 11(4), 766–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296817699637

- Reiterer, F., Polterauer, P., & Schoemaker, M. , et al. (2016). Significance and reliability of Mard for the accuracy of CGM systems. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 11(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296816662047

- Reddy N, Verma N, Dungan K. Monitoring Technologies- Continuous Glucose Monitoring, Mobile Technology, Biomarkers of Glycemic Control. [Updated 2020 Aug 16]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279046/

- Baron KG, Abbott S, Jao N, Manalo N, Mullen R. Orthosomnia: are some patients taking the quantified self too far? J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):351–354.

- Truong, K. (n.d.). What you need to know about this common sleep disorder. Do Sleep Trackers Cause Anxiety? Orthosomnia Explained. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/sleep-trackers-disorder-orthosomnia-meaning

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Diabetes distress and Depression. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/professionals/diabetes-discoveries-practice/diabetes-distress-and-depression

- Risk factors. National Eating Disorders Association. (2018, August 3). Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/risk-factors

14 comments

I started wearing a Fitbit in Spring 2020 and have found it really helpful to stay tuned in with my sleep patterns and overall activity level. I don’t feel a lot of anxiety when I don’t reach my goals on a specific day which is maybe just my personality. But it helps to have some data if I feel like I’m not sleeping as well consecutive days in a row or it will motivate me to get out for an extra walk if I haven’t been as active as I want to be. I also like being able to see my heart rate graphed out when I do a HIIT workout and I can easily check my heart rate while doing the workout and push myself a little harder if I want to that day.

“Do you think happy 100 year olds in Greece got that way with extensive food journals and continuous glucose monitors?”

I don’t think this is a good analogy. I think it fails to get past a correlation/causation test or really factor statistical variance. The better question would be “Do you think there would be more or less happy 100 year olds with or without wearable health monitors”. The vast majority of Americans live such an absurdly unhealthy lifestyle it is tough for me to imagine they wouldn’t get benefits. Imagine wearing a glucose monitor and drinking a 20 oz Dr Pepper. Further, the experts in some of these fields have a vested interest in not being partially replaced by smart technology. I think some of the concerns are valid but this isn’t a very well written article. Starting off with a poorly thought out question calls everything into question.

Thanks for sharing your perspective, Mark.

My daughter gave me a Fitbit for my birthday several years ago. I used it but found that it became one more thing to have to do – check exercise and sleep patterns and upload the info and compare my steps with hers, etc. It was like having a pet, so I gave it to my husband – the electrical engineer – who loves it!

Ha! Great compromise, Babz! It’s really about knowing what is best for ourselves.

I started wearing a garmin watch recently hoping that keeping an eye on my heart rate could help me learn to prevent crashes. After less than 48 hours I crashed and every day I got weaker. I kept wondering if it could be the watch and thought surely not. After 11 days I did find reference to the possibility of reacting to the Bluetooth connection and took the Garmin off. Within 3 hours I felt a little stronger, 4 days later I continue to improve. I’ve never had such a severe crash before, especially this time of year, ever. I did learn a couple of helpful things during this time.

Suzanne, interesting. Thanks for sharing this!

I found wearables really helpful as an athlete. Now that I can no longer be an athlete I find wearables discouraging. For example, when my Apple Watch admonishes me to be more active, it just reinforces the fact that I’m not able to do to chronic illness. I also used a sleep tracker when I first started AIP, and it really increased my stress and frankly interfered with my family life. The fact that the information was probably not accurate makes it even worse. For me, overcoming perfectionism was really important to my healing journey, and wearables just feed into it.

I have never used any kind of electronic tracker and don’t intend to. Tracking so much information about my body and looking at data would cause me too much anxiety. I think you have to know yourself if you can handle it or not. Low tech keeping a food diary and tracking how I feel after introducing a new food is helpful. I know if I slept well or not by how I feel. Simple journaling does the trick for me. Exercise some, go to bed and get up at the same time each day, connect with nature, eat a variety of nutritious foods and stick with your anti-inflammatory diet. Whatever’s on your list to help you. Check it off. So much easier for me. Less stress.

Laura, for the most part, I am on the same page w/ you. I do think knowing ourselves well & being able to be objective about it is key here.

I’ve had the same sort of experience that Kim mentions. If a FitBit or my Apple watch is encouraging me to get more steps in, but doing so would cause an autoimmune flare, then that really isn’t helpful. Worse, I’m the type of person who’s very susceptible to overdoing it so all I need is a little push to get me to overdo when really what my body needs is more rest. On the flip side, looking back at last month’s data regarding how active I’ve been vs. the month before that is a great way for me to see whether my energy levels (and so my health in general) is trending up or down. That can be really useful data if it lines up with changes in my routine, diet, medications, etc. I’d say tracking can be a good or a bad thing and I really need to be on top of managing it instead of letting it manage me.

I was given a Fitbit watch as a Christmas gift from my daughter. At first, I loved the idea of it recording my stats every time I played tennis, bike ride, or walked. And I enjoyed watching the calorie counter to see how many calories I burned. However, after a while, I felt that my health was being monitored by some outside source and the data is being transferred by some EMF force. I didn’t want to be exposed to more EMF force field, so I took it off and it is sitting in my drawer. I want to give it away but since it is a gift, I am going to hold on to it until a younger family member shows an interest in wanting it.

Diana, thanks for sharing your experience!

Last year I got a FitBit just to track my sleep. Before then, I’d have to remember every morning what time I went to bed and what time I got up and estimate how much sleep, and then I recorded a yes/no metric of whether or not I got enough sleep (7.5 hours). It was very inaccurate. After getting my FitBit, I discovered my estimates were off by almost an hour (mainly due to difficulty of falling/staying asleep and not clock watching). So now, I just put it on when I go to bed and it does it’s thing without my having to spend any time thinking about it. Success!